Introduction

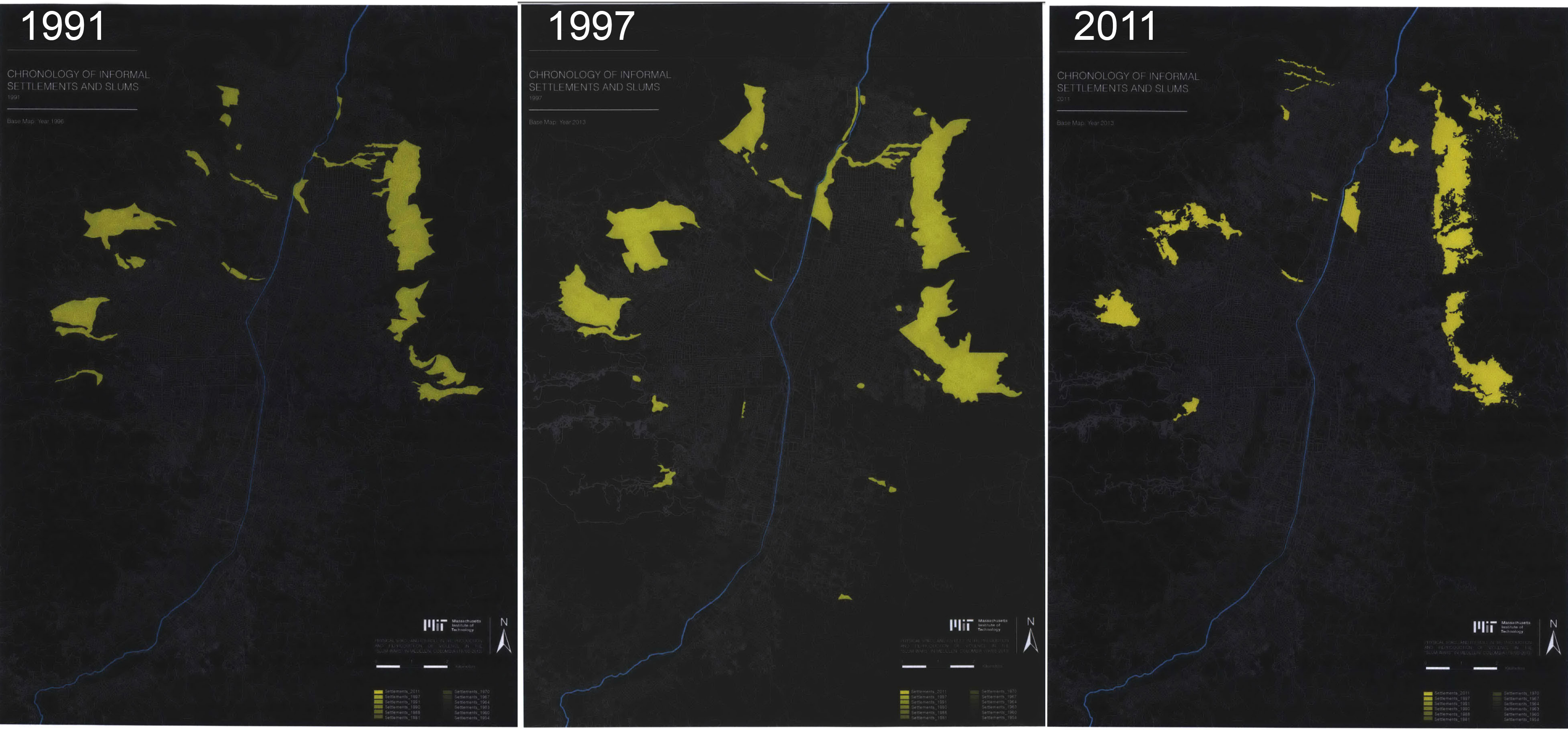

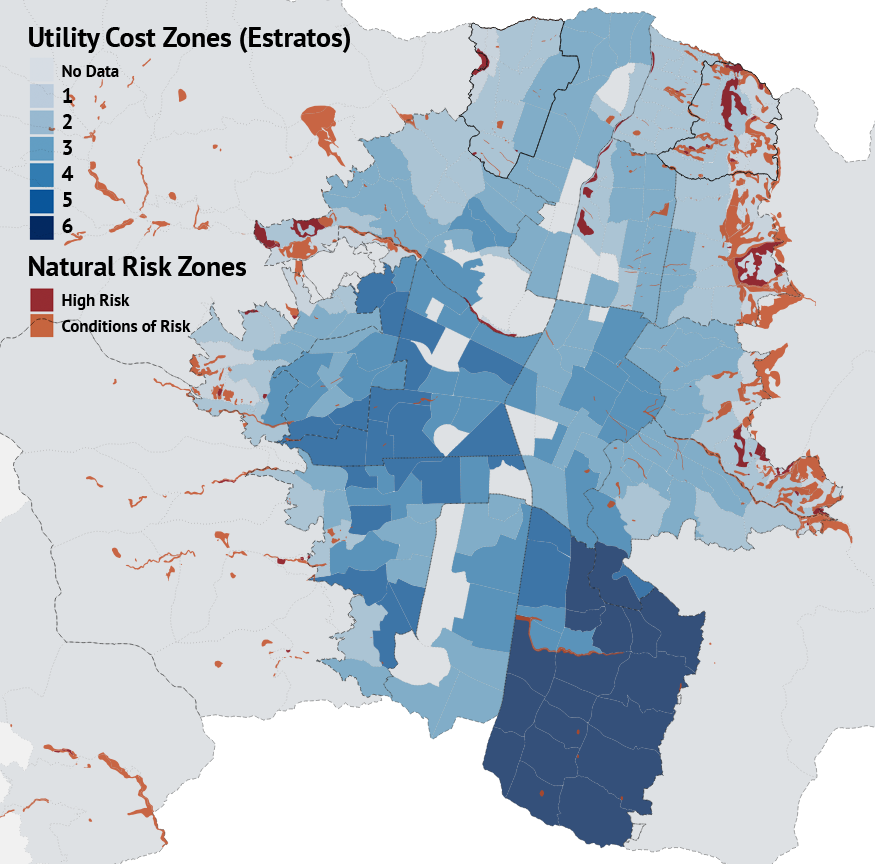

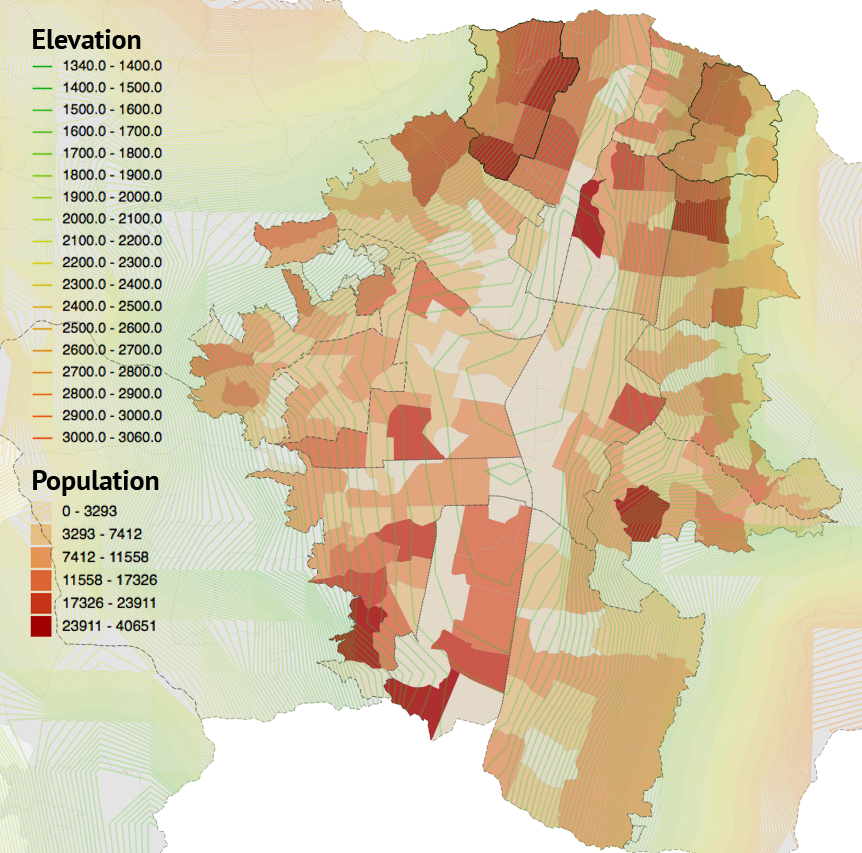

In his book The Colombian Conflict in Historical Perspective, Fernan Gonzalez argues that Colombia’s historic lack of strong centralized control has contributed to the 53-year conflict between guerillas, paramilitaries, and the state. The most violent city in Colombia, Medellin, provides an example of city efforts to combat violence through planning initiatives. We've specifically explored how government planning policies have impacted the growth of informal settlements on the northern fringes of Medellin, using two example neighborhoods: Popular in the east and Doce de Octubre in the west. Doce de Octubre was partially planned through city initiatives in the 1960's through 1990's, though the housing is largely informal. Popular grew organically, with winding and blind streets and alleyways, largely without the benefit of centralized planning initiatives until the recent PUI policy.In the 1960’s-1980’s, the northern barrios experienced sudden expansion and population growth. Some people migrated from rural areas looking for jobs in industrialized Medellin; some pushed outward from neighborhoods in Medellin that had become unaffordable. The population growth and informal construction in these regions has been categorized as “pirate” settlements. Popular and Doce de Octubre are two examples of illegal settlements located in the hills around the valley of central Medellin -- a feature that has made them difficult to control and monitor, difficult to access, and vulnerable to Medellin’s deadly landslides.

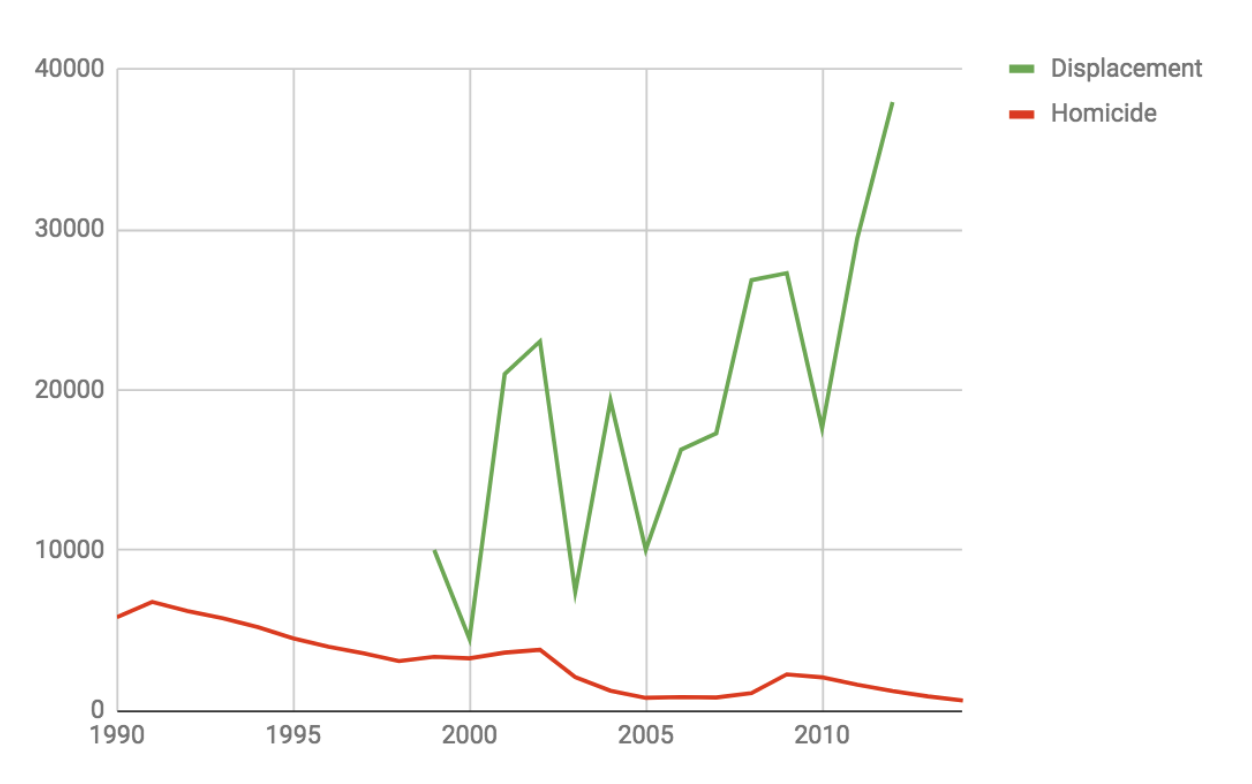

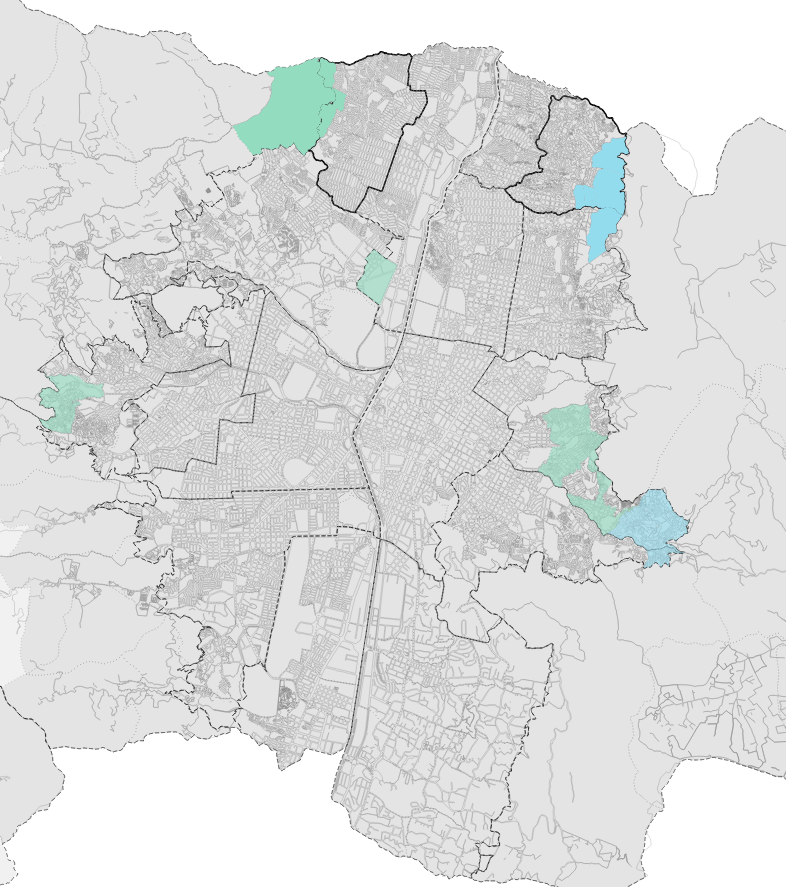

Because of devastating landslides in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and the growing threat of guerrilla presence in these remote neighborhoods, the government of Medellin began to ramp up intervention efforts in informal neighborhoods in the 1990’s with a program called PRIMED, and again in the 2000’s with the PUIs. Doce de Octubre experienced greater effects from the earlier programs, but Popular has been a neighborhood of particular focus for the PUIs. Homicide rates in these areas have historically decreased with greater government intervention; however, as homicide rates city-wide have decreased, internal displacement has risen. Gangs still control many neighborhoods of Medellin, using the same check-points as previous criminal organizations of the 1990’s.

PRIMED: Foreign NGOs and social capital

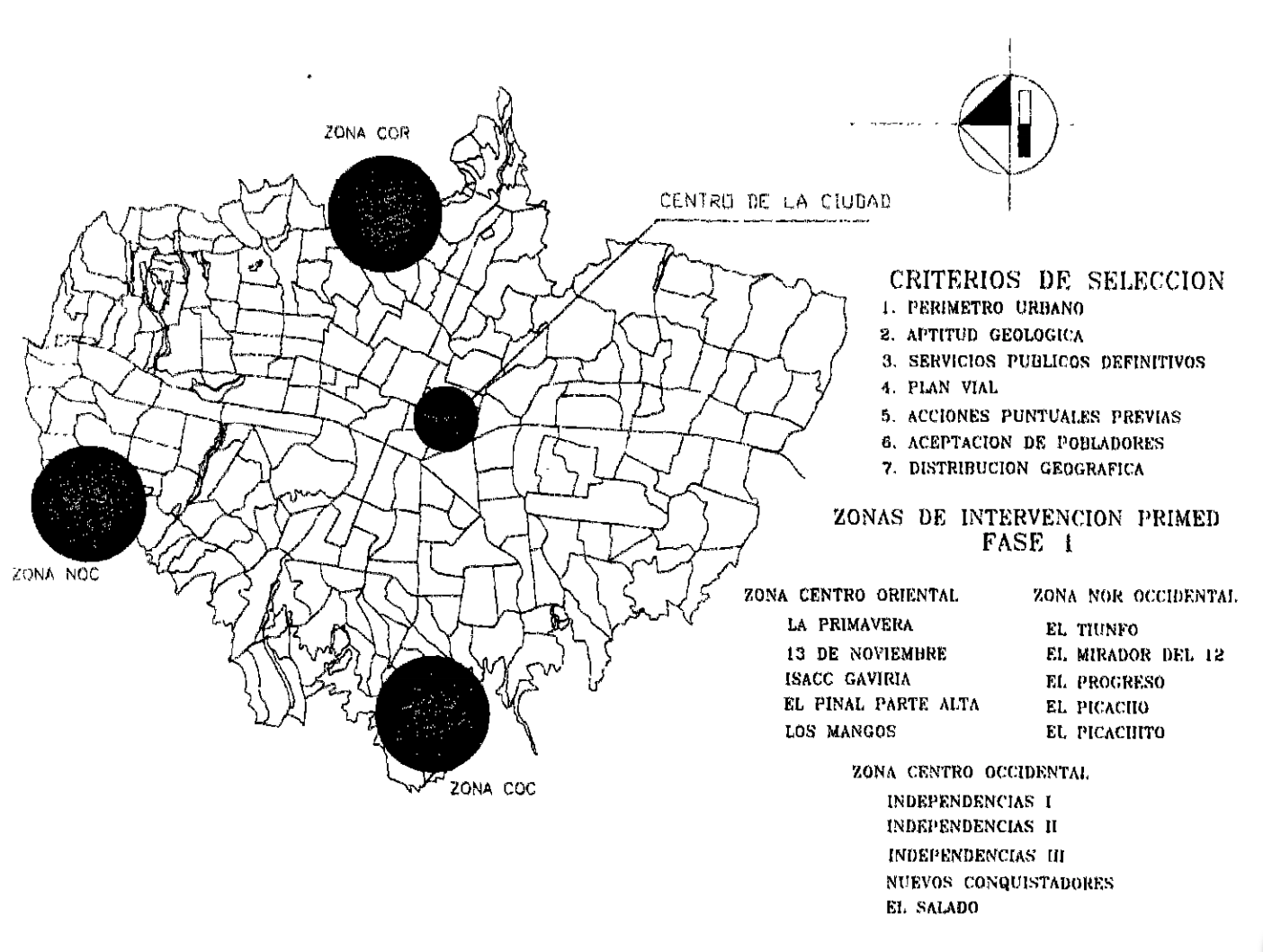

PRIMED, or Integral Program to Improve Subnormal Neighborhoods in Medellín (Programa Integral de Mejoramiento de Barrios Subnormales en Medellín), initiated in 1992 to address “subnormal” neighborhoods, characterized by the state as having informal housing and drug trafficking. People living in these areas were characterized as undereducated, with high unemployment rates, reactionary women and children, and many disaffected young men who would turn to gangs.These neighborhoods were often formed by people pushing out from the central city or immigrating in from the countryside. In the 1960’s and 1970’s Medellin’s central government was openly hostile to informal settlements, burning down the homes of people living there. However, after enough families had settled and staked a claim to the land, they were often able to block the government from this kind of action.

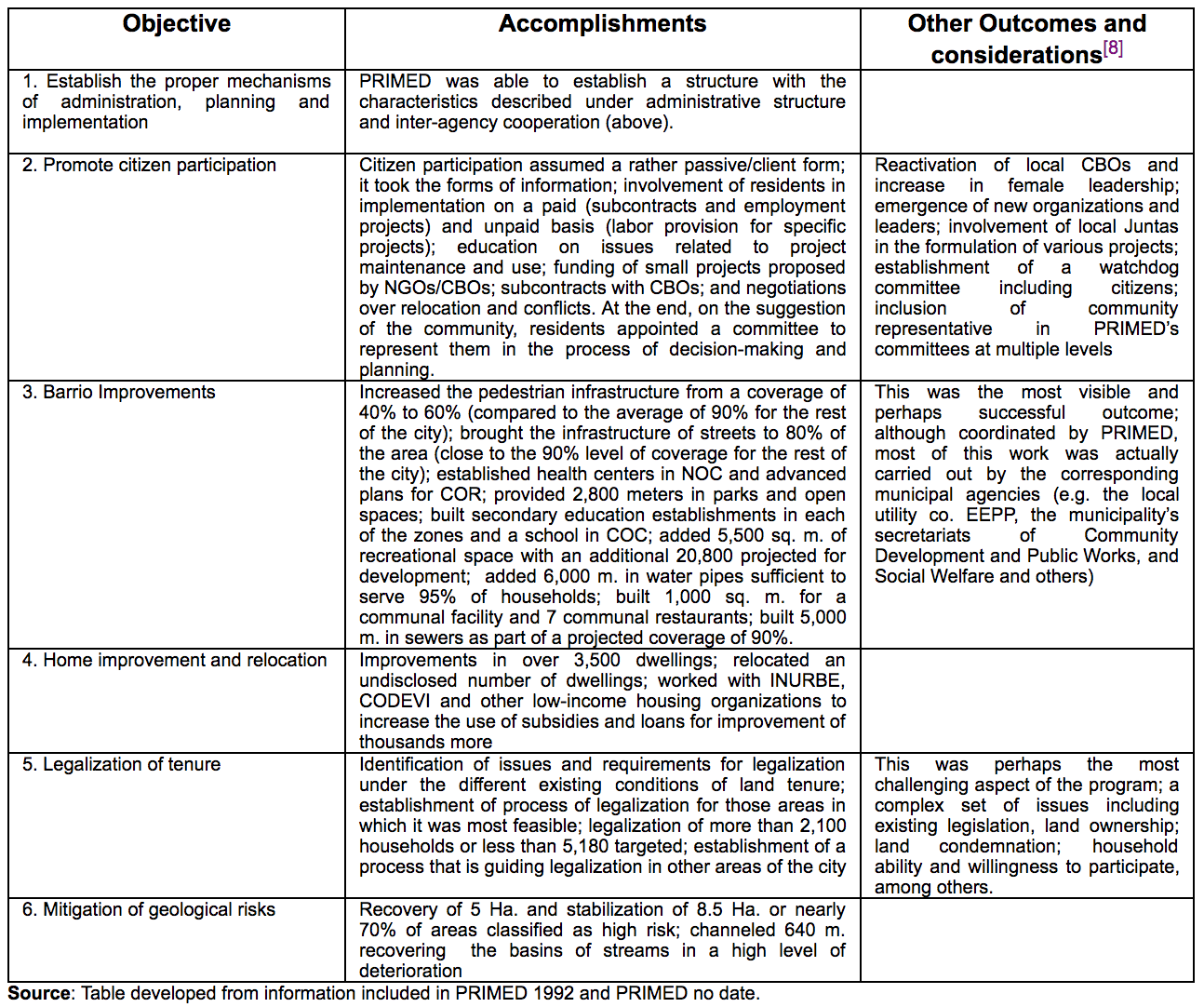

PRIMED opened local offices in their focus neighborhoods, mostly on the city’s western fringes, to build relationships with local community organizations and leaders. Through these partnerships they encouraged formal construction and urban development by granting land titles and subsidizing construction costs, while strengthening local organizations that would perpetuate the changes going forward. Once a neighborhood was deemed normalized to Level 1, PRIMED undertook to improve its planning, efficiency, and public space. This involved the Integral Urban Programs. The PRIMED Integral Urban Programs (also called Programs of Urban Improvement) trained local leaders to organize and unite their communities, and sought to integrate members of the community into PRIMED’s physical improvements of their neighborhoods. The idea was that members of the community would need to perpetuate the improvements after PRIMED’s initial interventions, and that increased community participation and communication would improve social conditions in the long run.

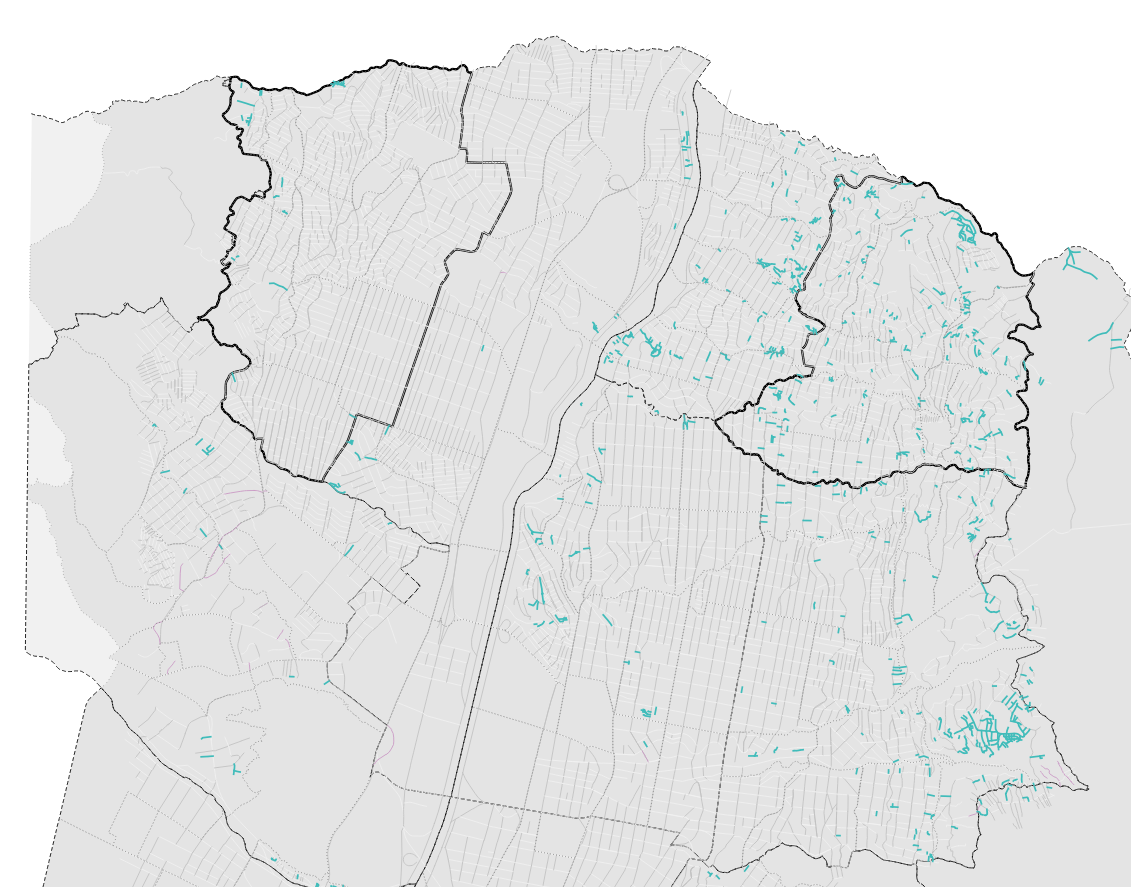

PRIMED Phase I focused extensively on Comuna 6 in the northwest. This neighborhood was settled in a combination of illegal, “pirate” occupation from internal displacement or rural migration, private ownership and development, and ICT planning and development. When PRIMED began to work with Comuna 6, many of the neighborhoods lacked basic infrastructure like water, and an estimated 58% of homes were illegally owned (without titles). Between 1993 and 1995, PRIMED invested 3,600 million pesos in improvement projects, including 160 meters of paths, 1,865 meters of aqueducts, 2,000 meters of sewers, 99 meters of walls to combat landslides, 147 linear meters of filters, and several soil and geotechnical studies to further combat landslide risk. Between 1995 and 1997, they planned to continue along these lines, bettering a total of 1,385 houses and relocating 199 from dangerous areas; as well as delivering 9,969 title deeds to houses.

Like the ICT, PRIMED focused its first round of efforts (1993-1997) in the northwest Besides the grids themselves, we can see the lasting effects of planning in Comuna 1 vs. lack of planning in Comuna 6 neighborhoods by looking at the concentration of easements in each. Easements refer to roads built across someone’s property, implying that the road was needed but not planned beforehand as part of a grid. Easements indicate areas of organic, rather than pre-ordained, growth. The two neighborhoods exhibit clear differences in the number and pattern of easements. Here we can see the evidence of ICT’s and PRIMED’s earlier planning efforts.

DDR and PUI: Guerillas, gangs, and demobilization

Medellin is a city that, like many others, was modified by a rapid urbanization process in which the government was not prepared to handle. Informal settlements were created and marginalized for years, resulting in the lack of formal political presence in these areas. At some point, gangs or armed groups replaced the government as providers of basic needs for the population, intentionally aiming to have control over these areas. This scenario was perfect for the rise of violence in the city.Beginning in the nineties, the city started the implementation of social and cultural projects to diminish the level of violence. Urban planning and renewal was used as a way to provide access to parks, plazas and city assets such as libraries, schools, playgrounds and other general open spaces. The integrated urban projects also provided the city, especially the marginalized and violent areas, with access to better transportation system and connection to job opportunities. Running parallel to that, the death of Pablo Escobar and peace agreements made with some of organized crime groups were essential to reducing crime.

Following the policies interventions during the 90’s, the first decade of the 21th century marked a significant decrease of violence in Medellin. In 2004, when the new mayor Sergio Fajardo took over, new methods of reclaiming government presence in informal settlements were put into work. His main goals were to reduce social inequality and violence in the city. By the end of 2007, for the first time, the homicide rates in the city were lower than the national rates.

Sergio Fajardo believed Architecture had the power to influence the quality of life in the low-income areas of the city. During his years in power, he started a plan for the construction of major infrastructure projects in these communities. At the same time, the mayor used new policies for the resolution of conflicts and to benefit residents with various resources for development. The combination of these two initiatives had a common goal of providing better education for the population. They were part of the program called “Medellin, la Ciudad más Educada”. We will be focusing on the DDR initiative and the Integral Urban Projects (PIU).

The DDR process initiated as a National Policy in 2003 during Alvaro Uribe administration. It started with a peace agreement between the government and Paramilitary group BCN. Mayor Sergio Fajardo took the challenge of continuing the implementation of this program in Medellin. By the end of his administration, Comuna 1 had 527 demobilized individuals, while Comuna 6 had 248. These numbers are not totally surprising, since Comuna 6 had historically been given more attention in regards to neighborhood development and state presence. The short-term success of the program could not be carried out for many years. Some authors and researchers on the subject are skeptical when analyzing the results of the program.

Definitely the big challenge was the years after the demobilization process and reintegration of members of armed groups into society. Employment accessibility after demobilization is crucial to that objective. In the case of Medellin, Mayor Fajardo developed initiatives for educational assistance as a way of keeping this people from going back to organized crime. But the characteristics of Medellin did have an influence in this process. Although paramilitaries were demobilized, less visible young gangs were still active in informal settlement neighborhoods. So groups who are in control of certain areas start to recruit young demobilized members, and these teenagers see these opportunities as a way of earning more money than they would in low-wage jobs. Samber Escobar, in one of his articles, explains that because of these various armed groups who are embedded in the urban fabric of Medellin, young members could be absorbed by them after demobilization.In addition, the program is seen as having a high political background, since the demobilization was addressed to only paramilitary groups, while violence was taken towards other groups. In that case, the continuity of the program would depend always on the party in power at the moment.

The program had controversial results in reducing the conflict and maintaining these actors out of the crime scene. Although people felt insecure with the paramilitary groups, a territory that was before controlled by them was now, after demobilization, under conflict between youth gangs for its control, which would potentially cause more violence. On the good side, some authors believe that the process helped to support the physical interventions, called PUI’s, on the low-income communities. The state had more control of the territory and could now implement actions within the community.

PUI

The PUI’s projects can be explained as physical interventions in the most marginalized areas of the city of Medellin with the objective of providing great quality of space for residents who previously could not have access. It was part of the Mayor’s plan for bridging the gap of social inequality and improve neighborhood connection to public services. As it was noticed, these projects are mostly related to bringing education for population, but ended up also having cultural and entrepreneurial characteristics. It is interesting to notice the correlation between PUI’s and PRIMED, having a strong inspiration in the earlier initiatives; in fact, Samper Escobar believes there is a continuity between these two projects due to the fact that some of the same researchers worked on both processes.

The PUI’s intervention included 5 libraries, 10 new public schools and renovation of 132 existing schools, development of public spaces, and transit oriented interventions. The libraries were designed by major architects from around the world as part of the mayor’s plan to bring high quality space to people who did not have access.

Conclusion: an Evolving Political Situation

The presence of state planning initiatives in marginalized neighborhoods has had significant impact on the their development. This history of urban intervention is evident looking at the fabric of these neighborhoods today. Thanks to programs like ITC and PRIMED, Comuna 6, Doce de Octubre, in the north-west, has more ordered streets, historically lower homicide rates, and a higher strata (wealthier) population than Comuna 1, Popular, in the north-east. The street grid of each neighborhood reveals this difference of planning, as Comuna 1 has winding and chaotic streets, while Comuna 6’s tend to be straighter. However, Comuna 1 also has more extreme topography, and the street grid is also simply responding to this geographic reality.More recently, government interventions such as the PUI’s and DDR have added transit options, green space, and new community centers to Comuna 1. The positive impacts of these new investments have been visible in Comuna 1’s decreasing homicide rate. From 1994, a year after PRIMED began, until 2008, Comuna 6 had fewer homicides than Comuna 1. However, beginning in 2005, a year after Sergio Fajardo became mayor, Comuna 1 has had fewer homicides than Comuna 6. The one exception was in 2010, when the homicide numbers of both neighborhoods nearly doubled.

So, do improvement programs really have an impact on safety of communities? What can be done different to achieve stronger results?

Although these informal settlement rehabilitation programs have had positive impacts, they are also the result of complicated political motives, and subject to the whims of administrative overturn.