Map of Redevelopment After Textile Mills Strike.

Introduction - How Did We Get Here?

How did Mumbai go from a port City full of textile mills, to the megacity it is today? The points referenced in the map above are where the city’s once thriving textile juggernauts stood. In their place arose newly constructed luxury buildings for Mumbai’s affluent population. How did Mumbai get to a place where luxury eclipses manufacturing? How did it get to a place where its poor and working class citizens basic right of housing is disregarded? This report attempts to get to the heart of these questions and foster further discourse on the realities of human displacement.Over the last century and a half, Mumbai has died and become reborn two times. The first death was in the late 19th century when almost 25,000 people were killed, and almost the same amount fled their homes, during the plague of 1896. The second death came nearly a century later after the textile mills strike of 1982. Close to a quarter million people walked away from their jobs for over a year due to poor working conditions and low pay. This strike ultimately shuttered Mumbai's textile industry as a whole. Although these events both resulted in great tragedy, the Mumbai that we know today would not exist without their occurrence.

As is similar in cities across the world, Mumbai's wealthiest hold power over the meek. Over the course of this narrative, the reader will be guided through a brief history of Mumbai and the tragedies that caused rippling changes to the City's economic and topographic landscape. Although my research will not be an all-encompassing journey, I hope to shine a light on areas of Mumbai's history that may not be readily known or widely available.

The 1982 Textile Mills Strike

The most recent death and rebirth in the City of Mumbai came in 1982. On January 18 of that year over 250,000 mill-hands went on strike at 50 mills across across the City to protest low wages, long hours, and a lack of health benefits. The workers’ who began the strike cried out for those who could not, beginning what is known today as the strike that broke Mumbai's great textile industry.Prior to the strike, Mumbai's business owners were kings. There was a massive surplus of workers and no regulation governing the their treatment. Most mill owners paid their workers monthly, to avoid absenteeism, required overtime work, and provided no health benefits. Workers often endured 16 to 18 hour work days in oppressive heat. The textile workers complained that the working conditions in the factories were oppressive, citing the system of montly pay as one that resulted in hardship and indebtedness.

1

As a reaction to these terrible conditions, a small collection of mill-hands formed a union and demanded more wages and better treatment. When their cries fell on deaf ears, they reached out to the union leader Datta Samant. Datta, fresh off of his victorious campaign getting the automobile union better wages and working conditions,

2

attempted to do the same for the textile workers union. After weeks of negotiations, and no movement on either side, Datta called for a strike.

The strike lasted over a year and a half with no movement on either side. The strike caused all 50 mills in Mumbai proper, and 80 mills overall, to close their doors. Even a year after the strike ended, approximately 150,000 workers remained unemployed or underemployed.

3

While the cotton and textile industry did continue after the strike had finished, it was never the same. However, even in the wake of this booming industry, Mumbai was able to transform into a megacity.Striking Mill Workers

Source: Gurgaon Workers News

Source: Gurgaon Workers News

Redevelopment Post Strike

The shuttering of the textile mills in the wake of the strike brought an end to a once lucrative industry, leaing to mass unemployment and a city in crisis. As a City, Mumbai had to quickly dig itself out of the trenches and find a way to rise from the ashes. In the era of revitalization and gentrification, most urban cities refurbish their older manufacturing buildings into posh residential and commercial real estate, and Mumbai has been no exception to this trend. This type of development often attracts wealthy investors and affluent buyers.Approximately ten years after the strike Mumbai established a second redevelopment plan, originally slated to cover the only first few years of the 1990s. However, the plan was utilimately transformed from short-term to long-term, extending to cover 20 years.

4

As with any redevelopment plan, the more far-reaching the plan, the less likely its goals will be realized. In Mumbai's case, only 12-14% of the total land acquired has been slated for redevelopment as of 2009.5

The plan has worked to shift Mumbai's economic focus from manufacturing to financial and high-level services.6

A change which the City's government hopes will attract multi-national conglomerates who focus on high investments and high returns.

However, as with any large scale change this shift has taken a lot of time. While the multi-billion dollar deals are being negotiated to bring investors to Mumbai, the monetary value of the mill structures continues to depreciate. Simply put, “the value of the mills, even as historical and cultural relics, has waned significantly, whereas the value of the land they sit on has skyrocketed."

7

However, many of the shuttered textile businesses were rented to the business owners from the City of Mumbai. When the business went under, the city reaped the benefit. The City, and others who owned property in Mumbai during this period, made millions, or even billions, selling to foreign investors. This cycle has perpetuated Mumbai's significant levels of income inequality; with the City growing essentially off the backs of the poor.World One Tower - Touted as largest residential building in the world

Source: Mega World via YouTube

Source: Mega World via YouTube

The 1896 Great Plague

To show that history loves company, let’s go even further back in time to investigate the first Mumbai death and rebirth – the 1896 Great Plague. Mumbai’s population exploded over the course of the 150 years preceding the Great Plague. As the population grew, disease, infection, and death began to grip the city and on September 23, 1896, Dr. Acacio Gabriel Viegas diagnosed the first case of the Black Plague in a small eastern neighborhood in Mumbai. Before the outbreak was able to be contained, over 25,000 people died and 15,000 fled in fear.8

The Black Plague hit Mumbai's most vulnerable populations especially hard, with the vast majority of the working class poor succumbing to it.

Fear-mongering played a major part in the rampant spread of this plague. There had been “a long-standing assumptions that viewed epidemic diseases as a product of locality-specific conditions of filth and squalor exercised a significant influence over the colonial state's war against plague."

9

This assumption led to the notion that environmental factors were the predisposing cause of the plague, and not necessarily the by-product of a larger economic failure. Even in the most scholarly literature, “there has been a pervasive assumption that colonial plague policies were predicated on the belief that the disease was contagious...transmitted either directly or indirectly through human agency."10

Even further, it was generally accepted that the disease was born from those who lived in filth and generally poor sanitary conditions instead of the actual cause, infected rodents and the excrement they produced, which was ingested by the working poor because of the conditions in which they had to live.

Because of these assumptions, according to Kidambi, “...there are significant links between the prosecution of plague policies in the late 1890s and the discourse and practice of sanitary regeneration in the city during the first decade of the twentieth century."

11

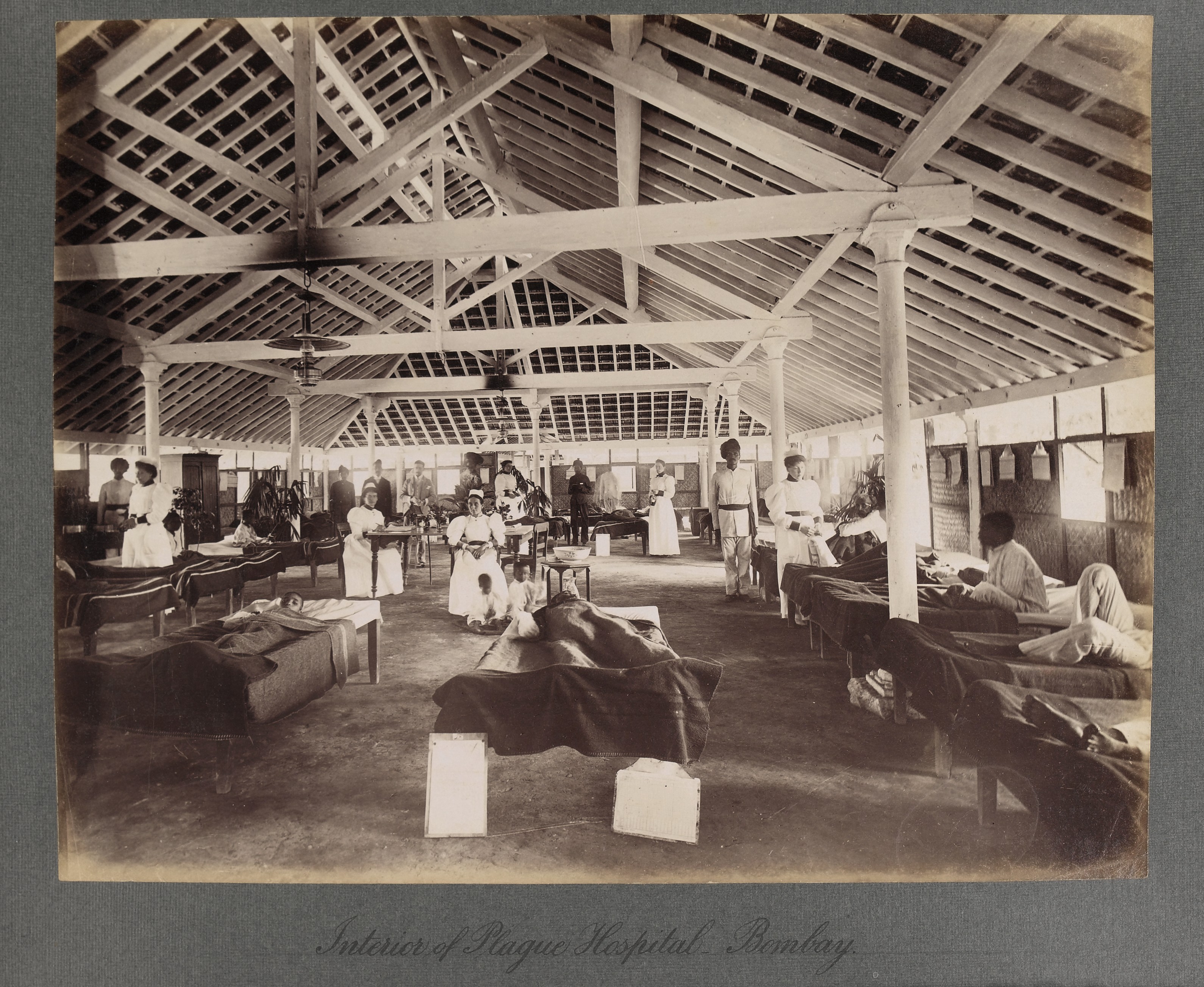

In short, the working class was deemed expendable and this throw-away mentality created the narrative that shaped significant policies for decades after the plague was contained.Interior of Triage Tent for Plague Victims

Source: Welcome Trust

Source: Welcome Trust

Redevelopment Post Plague

At the height of the plague, Mumbai (then known as Bombay) created the Bombay City Improvement Trust (BCIT) to spearhead the eradication of insanitary areas and create a plan for the general redevelopment of the city. The BCIT was established on November 8, 1898 and had six key principles: slum clearance and the improvement of specific areas represented by the Municipal Commissioner as insanitary; construction of new east-west thoroughfares, running from the densely congested inner districts of the Indian Town towards the seaboard; providing more building sites; provisioning sanitary housing for the poorer and working classes; developing government owned vacant lands; and providing new housing to the city's police force.12

Essentially, the BCIT’s expressed job was to redevelop the City.

As with any urban redevelop project, it is likely that through this process people will be displaced. In this case, as in most, it was the working class poor. While the BCIT did create homes for a portion of the working class, they soon became as unpopular as the plague itself. As Burnett-Hurst eloquently referenced, “The compulsory acquisition of property and the demolition of buildings were resented by both landlords and tenants. The Trust was also regarded as having usurped some of the duties of the Municipal Corporation. At the same time, it found itself considerably handicapped. The Municipality continued to exercise control over building by-laws and the general sanitary administration of the city."

13

They had just enough power and influence to cause damage, but not enough to affect change. Both the BCIT and the Municipal Corporation attempted to improve the livelihood of the working class, and the city as a whole, but fell short because of intra-office mismanagement and inter-office politics.One of the Municipality Offices of Mumbai

Source: Pinterest

Source: Pinterest

Railroads

This constant death and rebirth begs the question; how did Mumbai grow to such proportions?Mumbai was founded as Bombay in the early 16th century, growing rapidly in its' first couple hundred years. As with any newly founded city, Mumbai struggled to find its place amongst the larger, more established cities of the time. Because of its rich soil and close proximity to multiple ports, Mumbai quickly became the primary destination for manufacturers. In the early- to mid-19th century, plans were considered for the first railway system in Madras in 1832.

14

While this and other railways were not directly within Mumbai city limits, they laid the foundation to bring in new business.

The first passenger rail route within Mumbai traveled to nearby Thane on April 16, 1853.

15

This ultimately led to a series of railways that bifurcated the City, separating those who have from those who have not. Over the course of the next several decades, a total of six workshops employing nearly 18,000 men were established throughout the island city.16

The most powerful of all workshops were owned by the Bombacy, Baroda, and Central Indian (BB&CI) Railway and Great Indian Peninsular (GIP) Railway. The workshops of both "...were principally concerned with 'fitting up locomotives, building carriages and wagons, and carrying out general repairs.'"17

The railways continued to grow in popularity, becoming even more lucrative to business owners. The saavy owners found ways to utilize both the rich agricultural environment and the benefits of the new railway system, eventually erecting the City's thriving cotton industry was born.

Cotton Mills

As the mid-19th century progressed, Mumbai entered the cotton import market after the railways proved to be a viable mode of transportation and trade. "A Parsi entrepreneur named Cowasji Davar founded the first cotton-textile mill in 1854..."18

, naming it "The Bombay Spinning Mill."19

Within the next few years, Mumbai would slowly become one of the world's leading cotton exporter. By 1860, with only a 20% share in the market, Mumbai became the third largest cotton market in the world behind only New York and Liverpool.20

With the American Civil War, which started in 1861, came blockades at Confederate ports. These blockades effectively cut off the Northern United States' supply of cotton, forcing them to turn to India, and more specifically Mumbai, for this valuable commodity. By the end of the war in 1865, Mumbai had earned approximately 70 million pounds sterling, approximately 100 million dollars, in the cotton trade.

21

Unfortunately, once the war ended, the need for such vast quantities of exported cotton subsided. This change in demand prompted large traders to come up with new profitable business models.

Two new developments, the creation of the Suez Canal and the diversification of resources, helped Mumbai's textile mill owners keep the cotton industry profitable. The Suez Canal is a man-made waterway connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez, allowed business owners to thrive even though demand was low. The canal opened in 1869, significantly reducing the time needed to transport goods to London, and making the use Bombay's port facilities more viable.

22

Once this new route was established, business owners used the profits they earned to invest in more cotton mills, gaining economic advantages over their competitors while at the same time taking less risk by diversifying their resources.23

With this resurgence of new industries came more job opportunities, and also more people. Because of this, the cotton mills affected 'a wide range of trades and occupations' within the city. Thus, the state of the cotton trade 'determined levels of employment in the docks and on the railways,'24

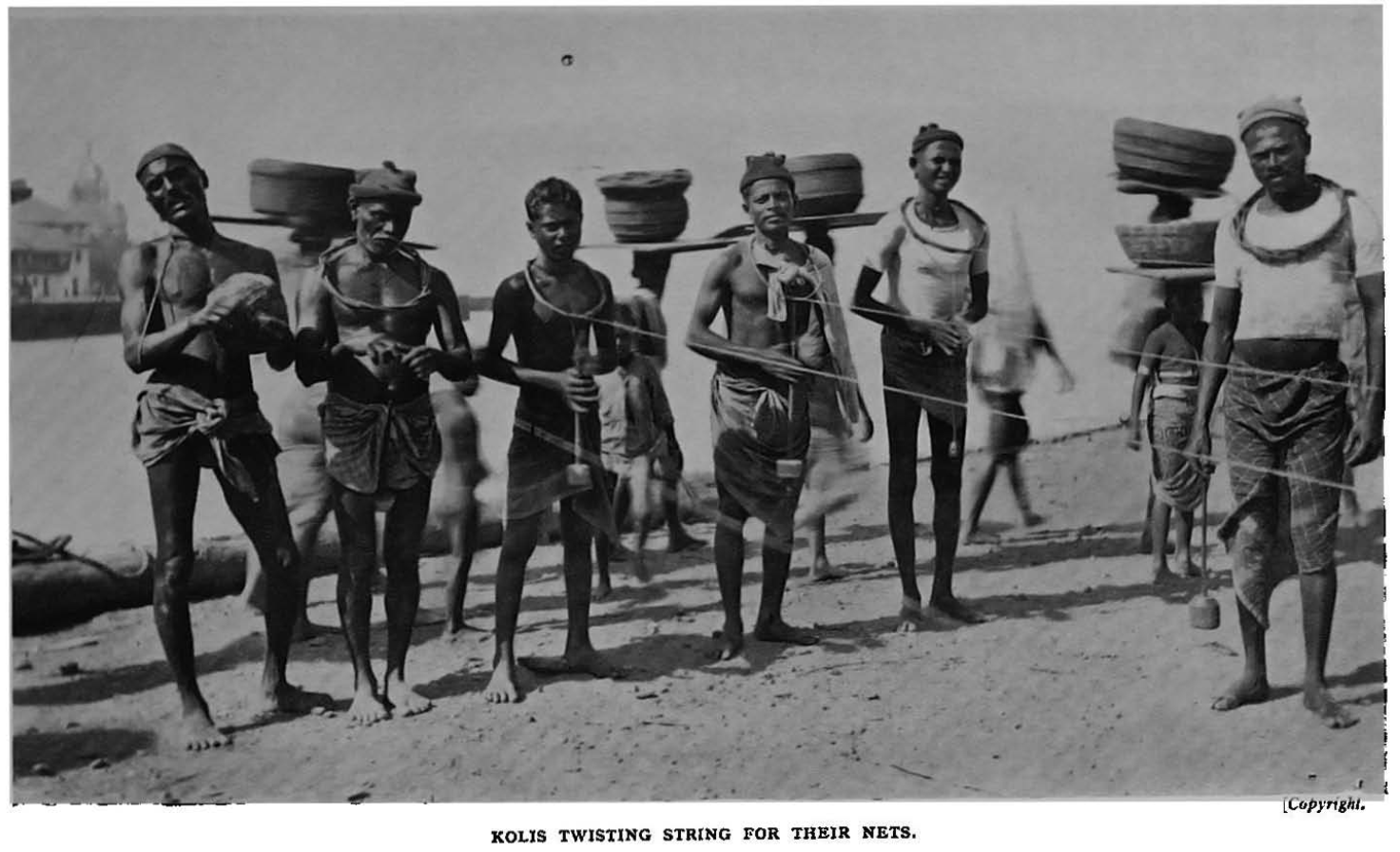

leading to the boom in Mumbai's population that lead to the catastrophic deaths outlined earlier.Kolis twisting string for their nets

Source: Burnett-Hurst, "Labor and Housing in Bombay"

Source: Burnett-Hurst, "Labor and Housing in Bombay"

Population

Once the word of these opportunities surpassed Mumbai’s borders, there was no holding back the flood of people looking to make a better life for themselves and their families. During my research, I came to the stark realization that no one agency has credible population data for this specific time period. While official census data is only available from governmental sources as far back as 1971, I was able to data mine population information as far back as 1872. To this end, I was able to approximate Mumbai’s population dating back to the early part of the 19th century.According to Gerson da Cunha, “in 1814 the population of Bombay was about 200,000, and the tenements 20,000. Now [approximately 1900] the population has quadrupled, and the number of buildings has nearly doubled."

25

Consider that for a moment. In the early part of the 19th century, the approximate population density was about 10:1 (person per tenement). By the end of the century, that figure doubled. That may not seem as a significant jump; however, this surge in residents had a massive impact on a city that ill-equipped to handle such a spike.

Surrounded by water, Mumbai has finite amount of land available to develop. Therefor, as the need for more housing grew, the city built up instead of out. Towards the start of Mumbai’s industrial revolution, most of the tenements were one- or two-story buildings, at the height of this period, there were thousands of buildings averaging five or more stories.

26

Landowners and business owners had to quickly find ways to house their workers, while still maintaining a profit.

The working poor, who immigrated to Mumbai from neighboring countries, found housing by living with family, friends or in other rentals. The three main types of housing available to the working class immigrants included: chawls – dilapidated structures in areas designated as slums, the vast majority of the working class lived here; sheds built of iron, tin, or wood by the Bombay City Investment Trust; and zavil sheds constructed of dried leaves – this was the worst kinds of structure, available to those who could not afford to live anywhere else.

27

As one can imagine, the vast majority of these makeshift housing structures did not have proper sanitation or ventilation. As the numbers grew, so did the number of sick and dying. Prashant Kidambi penned, “The city's modernization had resulted in 'two Bombays': the one inhabited by a cosmopolitan elite that nestled in the fashionable western enclaves of the city, the other 'full of chawls, crowded, insanitary, ill-ventilated slums, and filthy lanes, stabled and godowns, a city in which a vast proletariat was penned together and savaged together by disease.'"

28

This goes hand-in-hand with the bifurcation of the city vis-à-vis the newly constructed railroad. Those privileged enough to afford to live on the western spur of the railways lived a sheltered live in comparison to the working class.

By the mid to late 19th century, government officials were concerned that Mumbai would fall under the weight of its population. Two water works schemes (Tulsi and Tansa) were undertaken, starting in the early 1870s.

29

The schemes were designed to bring water to the masses. Most of the city could not afford private water connections and had to resort to using water from dipping wells. However, this water was so impure as to considered downright poisonous.30

An even larger threat to the health and well-being of the working class population was the seepage from drains, sewers, and sullage outlets into water pipes. Even if one could afford a private water connection, because of the close proximity to the sewer drainage, the water that came into the housing was never clean or fit to drink.31

Towards the latter part of the 19th century, a new Municipal Act of 1888 was created to attack this sanitation crisis from three fronts: elect or appoint a 72-person body, called the Municipal Corporation, to oversee the financial soundness of the city; create a Standing Committee that audited the financial accounts of the Corporation; and create a Municipal Commissioner responsible for carrying out the provisions of the law.

32

Unfortunately, this body was ill-equipped to handle the task of maintaining and managing the city’s civic and sanitary needs because of their conduct, compulsion, and constitution.33

During the latter part of this century, hundreds of working-class residents of Mumbai died because of inadequate living and working conditions. Unfortunately, this was only the beginning.People Walking In Waist-High Water

Source: Defence.pk

Source: Defence.pk

Conclusion

While every city deserves the right to reinvent itself, the cost to its population must be considered. Over the last 150 years, Mumbai has reinvented itself to ultimately become one of the world’s most powerful megacities. While their population continues to grow, albeit at a declining rate, their total population is well beyond what its geographic boundaries can support. The city is still divided in two; with a stark constrast separating the haves and the have nots. Those who have, have much more than they need. Those who have not, have nothing to lose. As Mumbai continues to develop into its next iteration, we can only wonder how long it will be before the next man-made tragedy throws the city into another upheaval.Please note: footnotes not visible on mobile.

Return to Student Projects