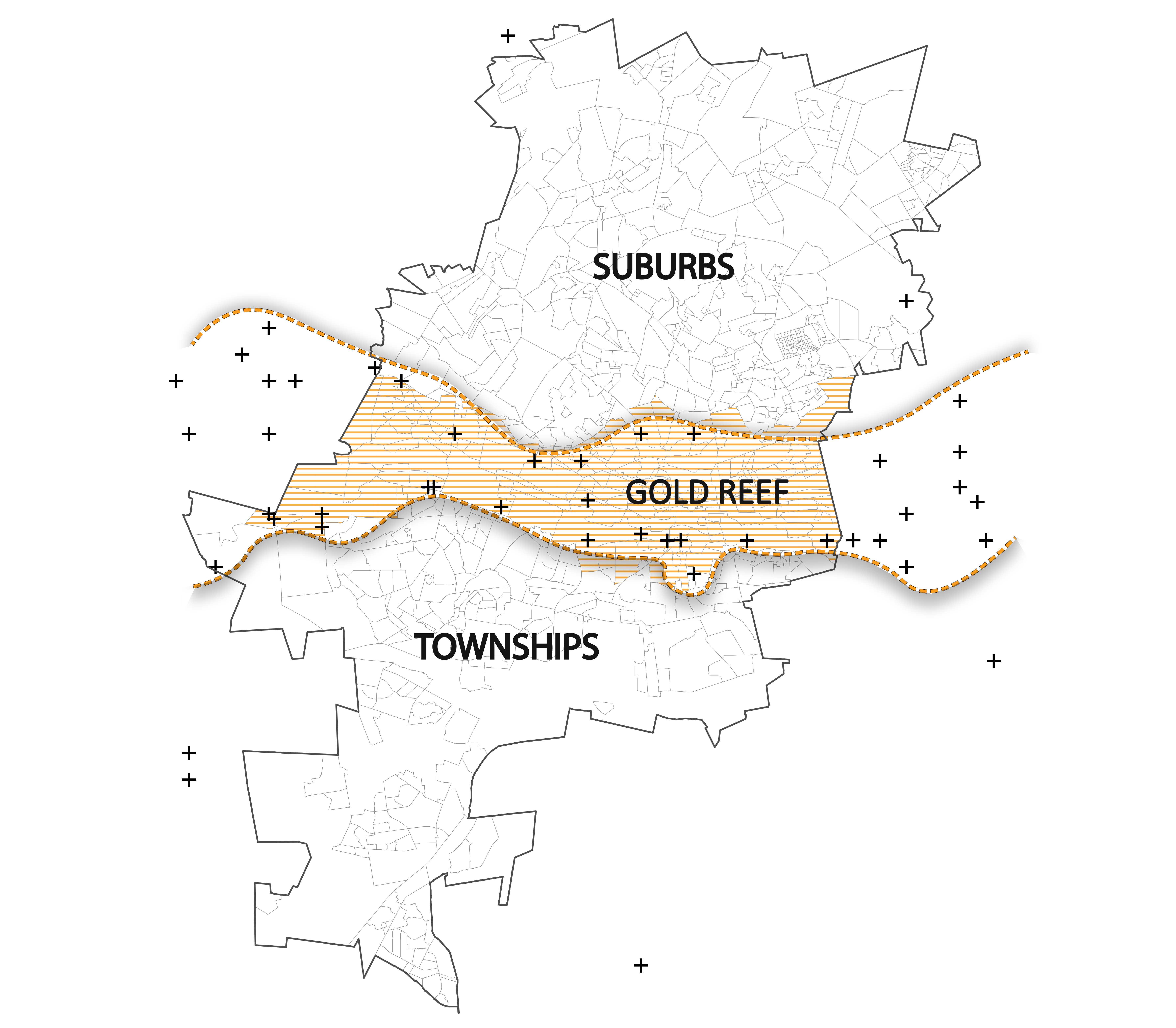

The Psychogeography Map of Johannesburg

Source: Daniel, Faux & Kannan

Source: Daniel, Faux & Kannan

Introduction

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

1

The physical landscape of Johannesburg, bisected by the gold reef lays bare a psycho-geography that stages a division of labor haunted by apartheid: the gold reef which measures more than 56 km separates the northern, more affluent (and more white) suburbs of Johannesburg — where wealth and capital are concentrated — from the more impoverished (black) South, the site from which labor is extracted. “The relations of production” — the totality of relations and bounds people are obligated to enter into for their survival — are put in relief by the mines and the slag heaps. Indeed, as Marx tells us, these social relationships are involuntary and they structure society’s economic base. The mine dumps—as much as the mines themselves — have shaped and continue to shape the ecological and sociopolitical landscape of the City of Gold, where the racial divide remains despite the promises of 1994. Robert Meister’s assertion that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission “reflects a post-revolutionary conception of justice as something other than a first step toward redistributing the illegitimate gains of past oppression”

2

is important, for the mine dumps themselves bear testimony to another broken promise of 1994: the South African gold mines were never nationalized.

The Smoldering Violences

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence

3

The task of historical materialism, wrote Walter Benjamin is to seize “that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to the historical subject in a moment of danger. The danger threatens both the content of the tradition and those who inherit it”(Benjamin 1940: 391).

4

But how to find words to narrate a violence that is incremental and unspectacular spectacular which is to say a ‘crisis’ that is not afforded the status of ‘crisis’ for it is smoldering rather than sudden? Indeed, the question becomes, can the minor event arrest—the danger not a moment but an accumulation, its effects “pervasive but elusive.”5

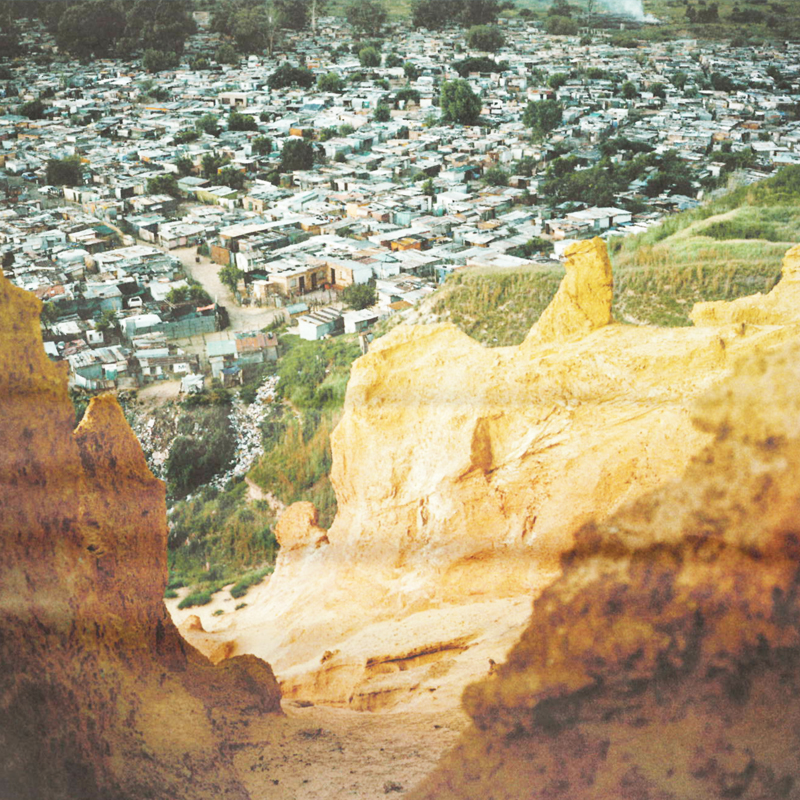

Image One: View from the top of a mine dump onto the informal settlement, Jerusalem. DRDGold owns this dump and wants to move the residents and reclaim the gold remaining in the sand.

Location: Off Witt Deep Roadm Delmore, Boksburg

Image Two: Silvester 42, and Todd, 21, have been fasting under this makeshift shelter on top of a mine dump for four days. The two men live in Soweto and come to the dump once a year to fast and pray.

Location: Off Harry Street, West Turffontein, Johannesburg

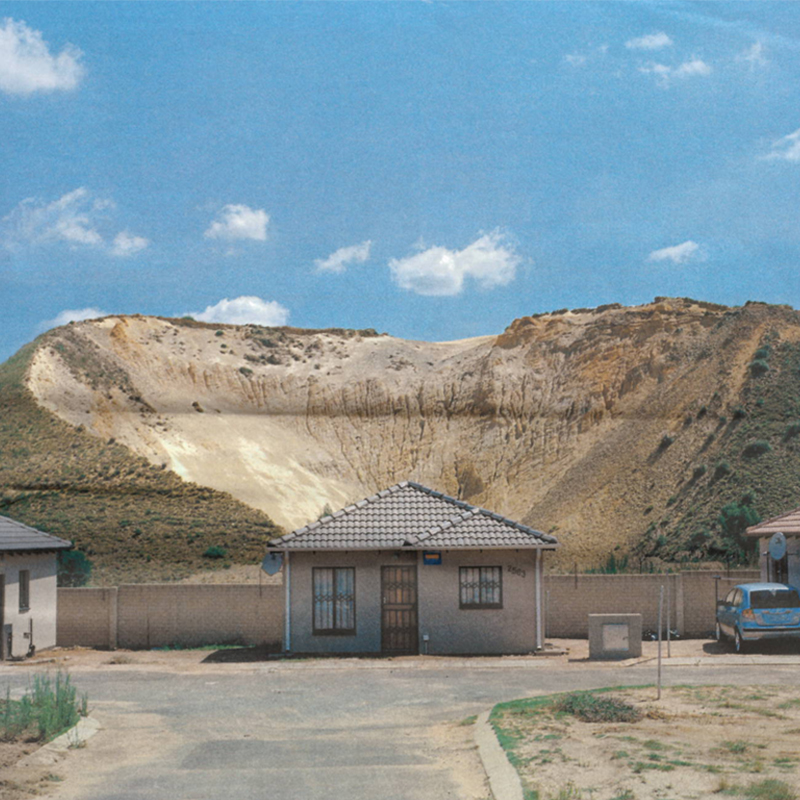

Image Three: New Affordable housing constructed in front of a mine dump that is being reprocessed for gold. Many commercial and residential developments are near, or on, old mining sites containing hazardous waste.

Location: Aalwyn Road, Riverlea, Johannesburg.

Source: "Tales From the City of Gold" by Jason Larkin

Location: Off Witt Deep Roadm Delmore, Boksburg

Image Two: Silvester 42, and Todd, 21, have been fasting under this makeshift shelter on top of a mine dump for four days. The two men live in Soweto and come to the dump once a year to fast and pray.

Location: Off Harry Street, West Turffontein, Johannesburg

Image Three: New Affordable housing constructed in front of a mine dump that is being reprocessed for gold. Many commercial and residential developments are near, or on, old mining sites containing hazardous waste.

Location: Aalwyn Road, Riverlea, Johannesburg.

Source: "Tales From the City of Gold" by Jason Larkin

Eerily beautiful, the. mine dumps are nonetheless vectors of toxicity. Acid mine drainage pollutes water indefinitely; Uranium seeps into the ground; while silicosis, the result of inhaling silica dust underground killed innumerable miners, dust particles from dumps saturate the air; those who live in settlements constructed on and around mine dumps bemoan a disturbing constellation of ailments ranging from birth defects to skin irritations to lung problems.

6

Contamination: On Seeing and Detecting

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag

7

Gednezar Dladla, Dust, TB and HIV

8

As a practice of visualization, mapping, has the ability to stage the paradox of what Rob Nixon calls “the long-term emergency" “long dyings—the staggered and staggeringly discounted casualties, both human and ecological—that are underrepresented in strategic planning and official memory.”

9

How a map is rendered, its resolution and color, for example, forces us to ask, what does it mean to see, and how does it differ from detecting? What is sensed in the form of asthma, tuberculosis, further comprise of an immune system already compromised by HIV— but not necessarily seen right away, since they result from an accumulation rather than a singular event?

On Seeing

High-resolution imagery from Google Earth, sourced from NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Landsat mimics how we “see” the earth

10

. The pixel resolution varies from place to place. Google buys satellite images from SPOT Satellite (and other companies) to get more high res. Therefore when you zoom into a place, the resolution is improved compared to the Landsat 8 imagery. The pixel size or spatial resolution for SPOT can get up to 2.5 meters by 2.5 meters.11

On Detecting

Low-resolution Landsat imagery, a “continuously acquired collection of space-based moderate-resolution land remote sensing data”

12

allows for the detection of phenomena that would ordinarily go unseen. Remote sensing is predominantly used in order to map environmental changes which includes but is not limited to fertile agricultural land, geological formations and mineral compositions of soil. The rendering of Landsat imagery can be either be natural or standard false color:

Laura Kurgen, Close Up at a Distance

13

What emerges from low-resolution imagery in standard-false color is the possibility to detect contamination, whose sociopolitical implications are wide-ranging. Standard false color is a form of language that allows us to detect that which we cannot immediately see.

The first image in the slider uses Landsat Combination 432. The second image in the slider uses Landsat Combination 753. Landsat Combination 432The use of natural colors in this image allow for it to be understood or decoded intuitively; brown is earth and vegetation is green. Landsat Combination 753This is an image rendered in standard false color, which defies being read intuitively. Healthy vegetation is bright green; grasslands will appear ‘normal green’; pink areas represent barren soil; oranges and browns represent sparsely vegetated areas; dry vegetation is orange; water is blue; sands, soils and minerals will appear as a multitude of colors. Here, cities and building blocks are ‘rendered out’ in order to render more perceptive urban and ecological changes. In the areas where mine dumps are located, it is likely that the blue represents acid mine drainage Source: USGS (United States Geological Survey) Landsat The Landsat Image Description:are taken at Path:170 Row:78 and Path: 171 and Row:78 Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS C1 Level-1

Image Four: The remains of Dump 20 that is being reclaimed by Gold 1. Once listed in The Guiness Book of Records as the largest man made heap in the world, it took nearly 60 years to create and contained 20 million tons of mining waste. It will take seven years in total to reclaim.

Location: Off Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road Randfontein

Image Five: This unlined pit between mine dumps is the receptor pit for neutralised acid mine drainage. Even after neutralisation, this every grrowing sludge and water mix has elevated levels of heavy metals like uranium, manganese, aluminium, lead, copped and cobalt.

Location: Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road Randfontein.

Image Six: Nicolle Madrice, 36, prays before collecting water from a stream heavily polluted by a mine dump owned by ERMP. Nicolle, a member of an African Independent Church, is encouraged by his church to collect fresh water daily for drinking, cooking and washing.

Location: Near Leeba Street, Meadowlands East, Soweto.

Source: "Tales From the City of Gold" by Jason Larkin

Location: Off Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road Randfontein

Image Five: This unlined pit between mine dumps is the receptor pit for neutralised acid mine drainage. Even after neutralisation, this every grrowing sludge and water mix has elevated levels of heavy metals like uranium, manganese, aluminium, lead, copped and cobalt.

Location: Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road Randfontein.

Image Six: Nicolle Madrice, 36, prays before collecting water from a stream heavily polluted by a mine dump owned by ERMP. Nicolle, a member of an African Independent Church, is encouraged by his church to collect fresh water daily for drinking, cooking and washing.

Location: Near Leeba Street, Meadowlands East, Soweto.

Source: "Tales From the City of Gold" by Jason Larkin

Click on marker for details on mines and related articles. Blue items represents pollution and environmental effects. Pink items represents illegal mining and mining related crimes. Yellow items represent dust pollution. Map best viewed full screen.

Money-Waste-Money

Achille Mbembe, Public Culture

14

Mines are haunted by their finitude, which is to say their eventual depletion. Until 2006, South Africa was largest producer of gold in the world. As of 2016 South African’s Department of Mineral Resources has identified thousands of mines deemed ‘derelict and ownerless’. According to the Chamber of Mines of South Africa, 562,000 times more waste than gold was produced in 2013.

15

In their “Mining Indaba” report of February of 2017, the Chamber of Mines predicts the imminent demise of mining:

"Looked at as a whole, with conventional mining [alongside full-mechanized mining], the industry can look forward to a sharp decline in gold production by 2019-20 and for mining to die out almost completely by 2033."

16

Once considered the detritus of a lucrative gold mining industry, in the age of global capital, finance capital, and speculation, the mine dumps have emerged as a source of profit. Advances in technology mean that dust can has the potential to be re-mined for precious metals. Vinay Gidwani and Rajyashree N. Reddy “contend that “waste” is the political other of capitalist “value”

17

, but in the case of the slag heap, forged is a relationship between surplus-value and waste, where the latter has transformed into the former, at least partially, with the passage of time. Indeed, extracted from a portion of the waste is use-value, which is what drives capitalist production’s drive to accumulate, which is to say generate surplus value. This transformation is mediated by what Achille Mbembe calls “superfluity”, which speaks to “to the dialectics of indispensability and expendability of both labor and life, people and things”.18

Ironically, risk—the neoliberal calculus of people over profit, has the potential to alleviate environmental dangers. Here, Rosalind Morris’ differentiation between danger and risk is useful. use[s]the term ‘danger…appl[ies] to the actual events afflicting people, and the term risk to its representation in terms of calculable and incalculable probabilities.”19

Image Seven: High-powered water canons are started in preparation for reclamation of a mine dump. About 30 bars of pressure we needed to break up and turn the sand into slurry, which is then transported to the processing plant where gold content is extracted. It will take four years to reclaim the remaining 4.5 million tons of sand.

Location: Viscount Road, near Main Reef Road, Randfontein.

Image Eight: Trucks transport sand from Dump 20, once one of the largest in the world, to trains that deliver the sand to the processing plant four kilometres away where any remaining gold is extracted. Gold 1 has been reclaiming the dump for six years, and has removed 17 million tons of waste. Rehabilitation of the land, earmarked for public open space, is scheduled to begin in 2018.

Source: Off Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road Randfontein

Image Nine: Admi, 38, collects material from a municipal rubbish dump to sell to scrap and recycling businesses, averaging a daily income of R150. Rubbish dumps like this on top of old mine dumps were sold or rented to the municipality many years ago by mining companies.

Source: Turffontein Road exit, Booysens, Johannesburg

Source: "Tales From the City of Gold" by Jason Larkin

Location: Viscount Road, near Main Reef Road, Randfontein.

Image Eight: Trucks transport sand from Dump 20, once one of the largest in the world, to trains that deliver the sand to the processing plant four kilometres away where any remaining gold is extracted. Gold 1 has been reclaiming the dump for six years, and has removed 17 million tons of waste. Rehabilitation of the land, earmarked for public open space, is scheduled to begin in 2018.

Source: Off Tweelopies Road, near Main Reef Road Randfontein

Image Nine: Admi, 38, collects material from a municipal rubbish dump to sell to scrap and recycling businesses, averaging a daily income of R150. Rubbish dumps like this on top of old mine dumps were sold or rented to the municipality many years ago by mining companies.

Source: Turffontein Road exit, Booysens, Johannesburg

Source: "Tales From the City of Gold" by Jason Larkin

Please note: footnotes not visible on mobile.

Return to Student Projects